The collection of bacteria that ordinarily inhabit your body are know as your microbiome. These bacteria can play a role in your bodily functions such as digestion and immune health. However, a disruption of the human microbiome can also occur and allow for diseases such as Clostridium difficile infection. It is important for humans to advance our understanding of the microbiome so that we know the exact functions of all these bacteria. We must also learn the causes of these disruptions (such as overuse of antibiotics) so that we can minimize their occurrence and further prevent disease.

Recently, a team of researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine discovered that the human microbiome is “churning out tens of thousands of proteins so small that they’ve gone unnoticed in previous studies.” According to the researchers, these proteins can be organized into over “4,000 biological families.” The proteins are believed to play a number of roles for the bacteria, but the one I found most interesting was the fact that many of these proteins are predicted to be involved in bacterial warfare. It would be interesting to see if an extraction of these proteins would allow for more effective antibiotics. The team believes that since the proteins are “fewer than 50 amino acids in length,” they were likely folded into unique shapes and overlooked as actual proteins, but if the “shapes and functions” can be recreated in lab, then they are likely to advance drug development.

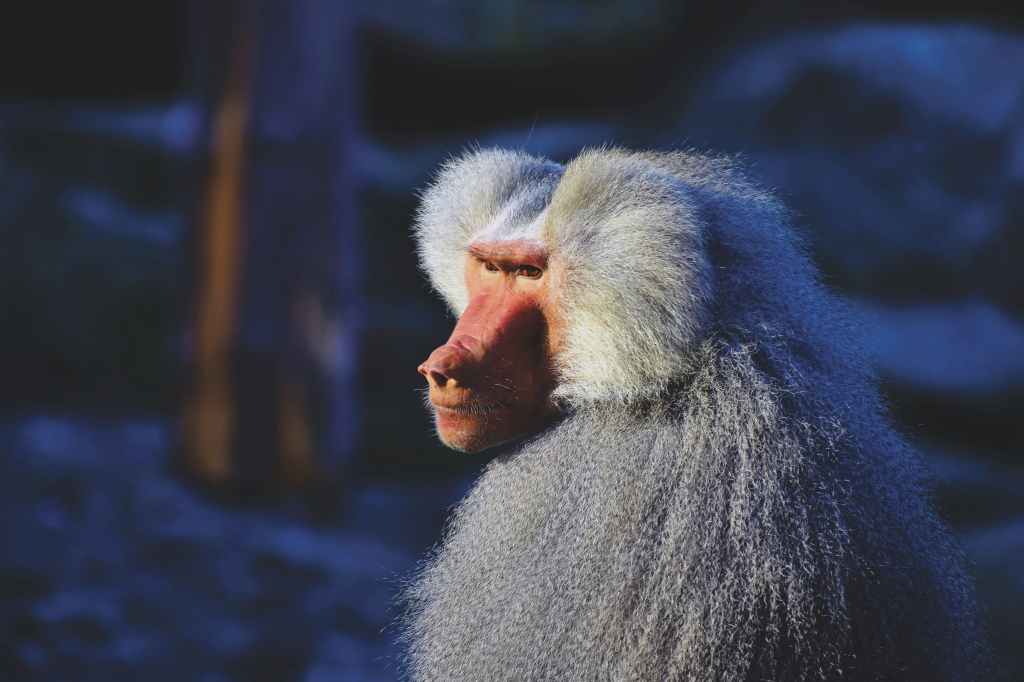

According to a recent study by Northwestern University, it may be important to look at “host ecology” when conducting microbiome research, particularly of the gut. The study examined how “Old World monkeys like baboons” have gut microbiomes more similar to humans than those of apes such as chimpanzees, which are more closely related to humans genetically. The researchers claimed that since the Old World monkeys have a more similar ecology and physiology to humans, then they should be used when studying the human gut microbiome. I think it would be interesting to know exactly what differences in habitat, diet, etc. would result in different microbiome compositions. It is also interesting that these researchers believe ecology is more important than genetics when looking at the gut microbiome, and makes me curious about whether there are different gut microbiome patterns between different cultures and ethnicities because of the same ecological differences? Hopefully future research answers this question.